The network is the innovation

What Thomas Edison actually invented — and what it tells us about the future of crypto

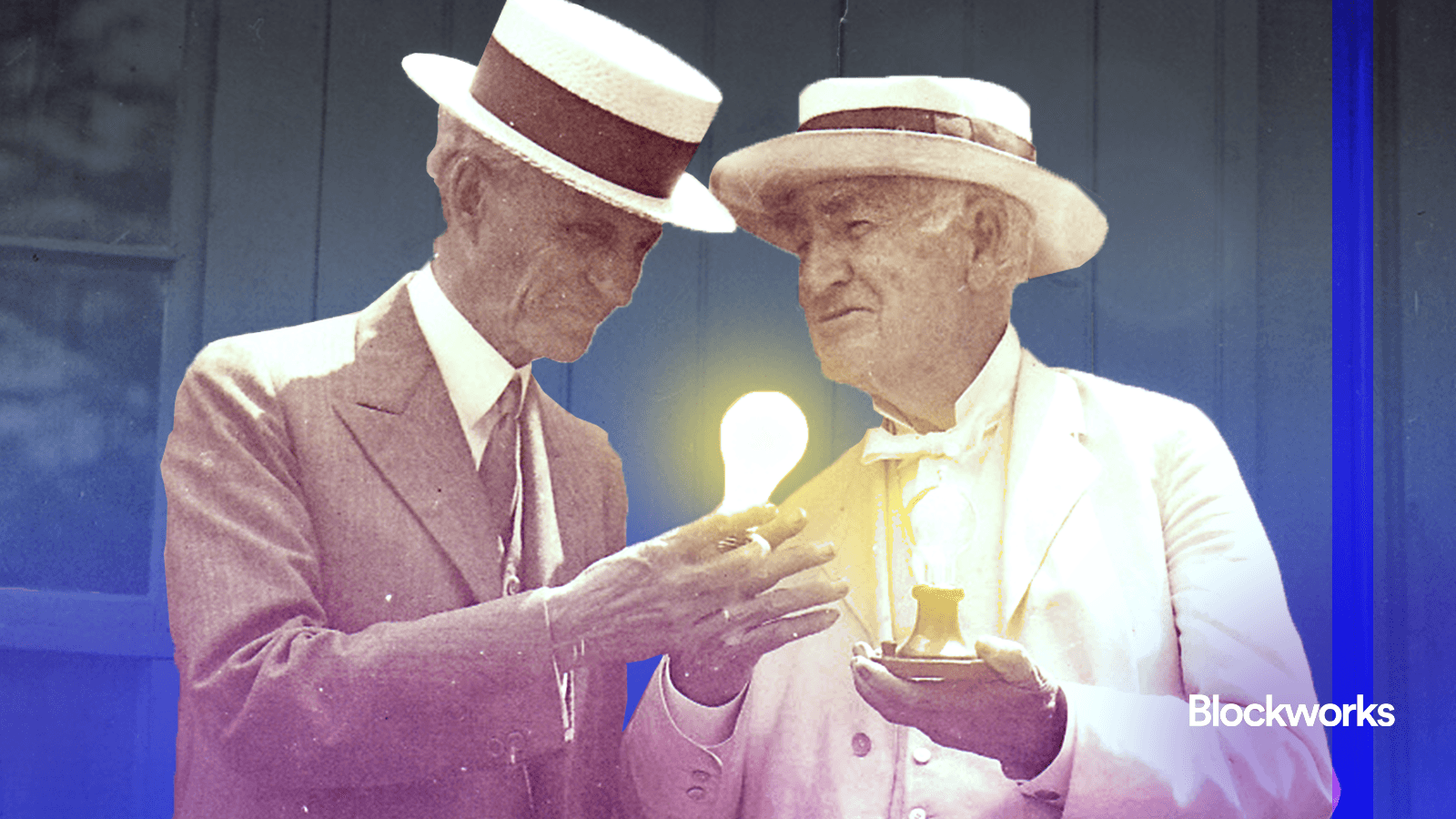

Henry Ford and Thomas Edison | U.S. National Park Service"Henry Ford and Thomas Edison holding incandescent lamps at presentation of Glass House."" (Public domain")

This is a segment from The Breakdown newsletter. To read full editions, subscribe.

“There was no lightbulb moment in the story of the lightbulb.”

— Steven Johnson, How We Got to Now

The lightbulb has come to be associated with serendipitous flashes of inspiration — the moment when a fully formed idea pops into an inventor’s head, prompting a shout of “Eureka!”

That’s not how the lightbulb itself was invented, however.

Popularly credited to Thomas Edison, the lightbulb was in fact the product of a century of trial and error by dozens of inventors around the world.

Electric light was first demonstrated by Humphry Davy in 1802.

The enclosed bulb mechanism was developed by Warren de la Rue in 1840.

Thomas Edison was born in 1847.

Many more contributed both before and after 1847 — the historian Arthur Bright lists about two dozen individuals as co-inventors of the lightbulb, with Edison’s work representing its culmination, not its origin.

“The Edison lightbulb was not so much a single invention as a bricolage of small improvements,” Steven Johnson writes in How We Got to Now.

Edison’s primary contribution to that bricolage was the late-1870s invention of the carbonized bamboo filament that ultimately made lightbulbs longer-lasting, safe for indoor use, and commercially viable.

But even then, Edison was forced by the patent courts to share credit with Sir Joseph Wilson Swan, whose version of the lightbulb was notable for being the first to light both a private home (his own) and a public building (the Savoy Theatre).

Hence the portmanteau naming of the “Ediswan incandescent lamp” that consumers were offered from about 1880.

This joint custody of the lightbulb takes nothing away from Edison’s achievements as an inventor.

Just the opposite — because Edison did something even bigger than bring artificial lighting to the masses: He industrialized the act of inventing.

“Edison didn’t just invent technology,” Johnson explains, “he invented an entire system for inventing, a system that would come to dominate 20th-century industry.”

That system inspired a proliferation of corporate R&D labs: teams of diverse specialists collaborating on problems, sharing financial upside, absorbing outside ideas, and freely building on each other’s work — a kind of “networked innovation” that’s infinitely more powerful than the popular image of the solitary genius inventor.

That, Johnson says, is the true lesson to learn from the story of the lightbulb:

“If we think that innovation comes from a lone genius inventing a new technology from scratch, that model naturally steers us toward certain policy decisions, like stronger patent protection. But if we think that innovation comes out of collaborative networks, then we want to support different policies and organizational forms: less-rigid patent laws, open standards, employee participation in stock plans, cross-disciplinary connections.”

And maybe crypto, too?

Crypto is first and foremost a way to incentivize the kind of open, composable innovation that builds powerful networks.

Edison proved that collaboration beats isolation, but his corporate model still relied on patents to retain proprietary control.

By contrast, the most transformative networks in history — Roman roads, standardized shipping containers, the internet, GPS — worked differently: They were open, permissionless infrastructure that anyone could build upon.

Christian Catalini makes the case for crypto by recounting the history of these open-source networks: “Money,” he says, “is the last closed network.”

And crypto is the way to open it up, to everyone’s benefit: “Permissionless innovation will always create exponentially more value than a closed system,” he concludes.

At the end of a disappointing year for open-source crypto, it’s worth remembering just how powerful these networks can be.

There was no lightbulb moment in the story of the lightbulb — and there may be no single moment when crypto “arrives” either.

Both are products of networked innovation that only realize their full potential when they become networks themselves — the lightbulb was merely a glass ornament until it was plugged into an electrical grid.

Crypto is building that grid for the digital economy — open, permissionless infrastructure waiting for the next great idea to plug in and light up.

Let’s hope it happens in 2026.

Get the news in your inbox. Explore Blockworks newsletters:

- The Breakdown: Decoding crypto and the markets. Daily.

- 0xResearch: Alpha in your inbox. Think like an analyst.