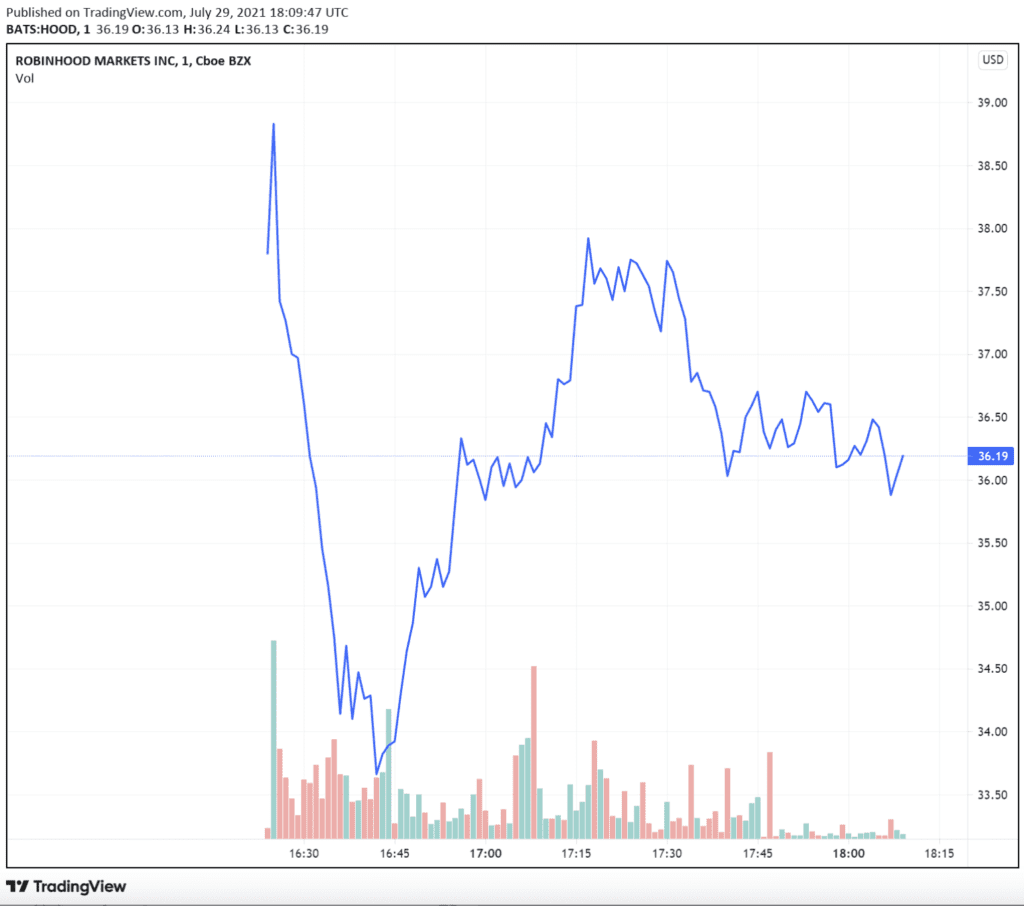

Robinhood Stock Slips on First Day of Trading

HOOD stabilizes at around $36, after dropping 10% on the opening bell

Source: Shutterstock

- Meme stock machine Robinhood was met with lukewarm interest from investors

- Robinhood has reserved a significant amount of shares for its clients and staff with an unorthodox lock up structure

Robinhood, the company that was at the center of January’s GameStop riot, hit the public markets today and investors didn’t seem keen on its promise to give more power to retail investors.

Shares of HOOD were listed at $38 — the low-end of that underwriters were pricing things at — and promptly fell more than 10% after the opening bell. The IPO valued the trading platform at approximately $31.8 billion. After the first few hours of trading, shares recovered to approximately $36.

Unlike many of the hottest tech IPOs, Robinhood is actually profitable.

Its S-1 form, filed in early July, showed that the trading company has 18 million retail clients, a triple-digit increase from 2020, and $80 billion in assets under its control. For the 2020 fiscal year, Robinhood reported a net income of $7.45 million on a net revenue of $959 million. In 2019, the company reported a loss of $107 million on $278 million.

Many tech companies that go public have a lock-up period for shares issued to employees in the private market. Robinhood is unique insofar that it has reserved shares for both employees and its clients, however these come with an unorthodox set of rules.

Employees will be able to sell 15% of their holdings upon public listing of the company, rather than after the usual six-month lockup period. After three months, employees will be able to sell another 15%.

Robinhood’s trading-hungry clients, of which around 35% of the shares are reserved for, however, will need to play by another set of rules. While there is no formal prohibition on selling the shares upon listing, the company said that those who dump their shares within 30 days of the listing will possibly be prevented from participating in other IPOs through the app for 60 days.

Regulatory questions cloud the IPO

All this comes as regulators take a hard look at the practice at the core or Robinhood’s business: payment for order flow.

While payment for order flow makes it possible for Robinhood to let customers place trades with no upfront commission payment, traders, and regulators are concerned that this allows the large institutional firms to see the data first before the order is executed. Effectively this makes the traders, and their data, the product as it can be mined for insights to perfect these funds’ trading algorithms.

In the case of Robinhood, Citadel Securities was a major order flow partner of Robinhood. In May, regulatory reports published by Robinhood showed that Citadel Securities paid Robinhood a king’s ransom ($142 million) for this data. Payment for order flow business generated Robinhood $331 million, Blockworks reported at the time. Of the $331 million, $142 million came from Citadel Securities.

Citadel, a separate hedge fund with the same founder as Citadel Securities, invested in Melvin Capital, the hedge fund deemed public enemy number one at the height of the GameStop fiasco, and was on the opposite end of the GameStop short.

“We think payment-for-order flow is a better deal for our customers, vs. the old commission structure. It allows investors to invest smaller amounts without having to worry about the cost of commissions,” Robinhood CFO Jason Warnick was quoted as saying during the company’s virtual roadshow.

But should regulators take a hard line on this, it would have a material impact on the company’s bottom line as it would be challenged to make trading available for free to clients as they are used to. Gary Gensler, the SEC chair, has long been a critic of the practice but it’s yet to be seen if the SEC will take any action on it.

HOOD is currently trading at $36.05 on the NASDAQ exchange.