The dollar needs a new bonfire of the bills

Powell is ending “run-off” to keep reserves “ample” — a far cry from colonial America, where fiscal responsibility was public spectacle

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell | Federal Reserve/"DSC_4206″ (US government work) and BLACKDAY/Shutterstock and Adobe modified by Blockworks

This is a segment from The Breakdown newsletter. To read full editions, subscribe.

Fiat money was invented in colonial America, and to convince people it had value, the colonies that issued it periodically lit their tax revenue on fire.

Paper money dates to 11th-century China, but historian Dror Goldberg argues that fiat — money valued primarily because the state demands it for taxes — was invented by the colony of Massachusetts in 1690.

Colonial Americans didn’t call it money at the time; to them, “real money” was metallic coins like Spanish pieces of eight, and the most-common form of paper their local governments printed was referred to as “bills of credit.”

But (as discussed yesterday) very little “real” money was available in the colonies, so bills of credit circulated as money instead.

Counterintuitively, when the bills circulated back to the government as taxes, they were burned.

This goes against our modern expectation of governments collecting taxes to use for current or future spending.

But at that early stage of monetary history, money-issuing governments knew they had to give people reason to believe the paper they printed in arbitrary amounts had value.

To make the public “cherish” its money, the government had to prove it could make that money scarce.

“Whereas it is of the greatest importance to preserve the credit of the paper currency of this colony,” the Virginia legislature resolved in 1760, “nothing can contribute more to that end than a due care to satisfy the publick that the paper bills of credit, or treasury-notes, are properly sunk.”

To that end, the legislature appointed a committee to ensure that, “at least twice a year,” all the bills of credit that had been collected in taxes were “burnt and destroyed.”

This bonfire of the taxes was often conducted in public, to make a memorable show of the government’s fiscal responsibility.

“The burning was an event,” Andrew David Edwards writes, “advertised in public newspapers and marked in legislative records.”

By making a public display of making money more scarce, the government hoped to maintain its value.

300 years later, that’s still sort of how it works.

Over the past three and half years, the Federal Reserve has “burned” about 2.4 trillion of the bills of credit (aka, dollars) it printed after the pandemic (in the form of bank reserves).

Technically, the Fed makes money more scarce by reducing the amount of debt it holds: US dollars are created when the Fed buys bonds from banks (which adds to banks’ reserves), and destroyed when the Fed lets those bonds mature (reducing bank reserves).

As a demonstration of responsible monetary policy, that’s not quite as dramatic as lighting bills of credit on fire.

Nor is the money destroyed very publicly: The Fed’s role in creating and destroying money did not get a mention in today’s FOMC’s statement, which announced only its decision on interest rates (a quarter-point cut).

In his press conference, however, Chair Powell additionally announced that the FOMC had decided to “cease run-off” of the debt it holds.

This is a modern way of saying it will not burn any more money.

In fact, it might soon be printing it again.

Reserves “have to be ample,” Powell said in the Q&A, adding that “at a certain point, you want reserves to start gradually growing.”

The Fed grows reserves by buying bonds.

In other words, the Fed will soon be printing money again (by buying bonds), because $6.6 trillion of bank reserves is no longer “ample” in today’s monetary regime.

There are a lot of monetary plumbing reasons for that, most of which are beyond my newsletter-writer understanding.

But the announced change of direction highlights perhaps the biggest difference between burning bills of credit in 1760 and reducing bank reserves today: It was fiscal policy back then and monetary policy now.

“Colonial Americans burned their money because each bill represented a tax debt that had been repaid,” Andrew David Edwards explained.

Of course, that’s not what’s happening now.

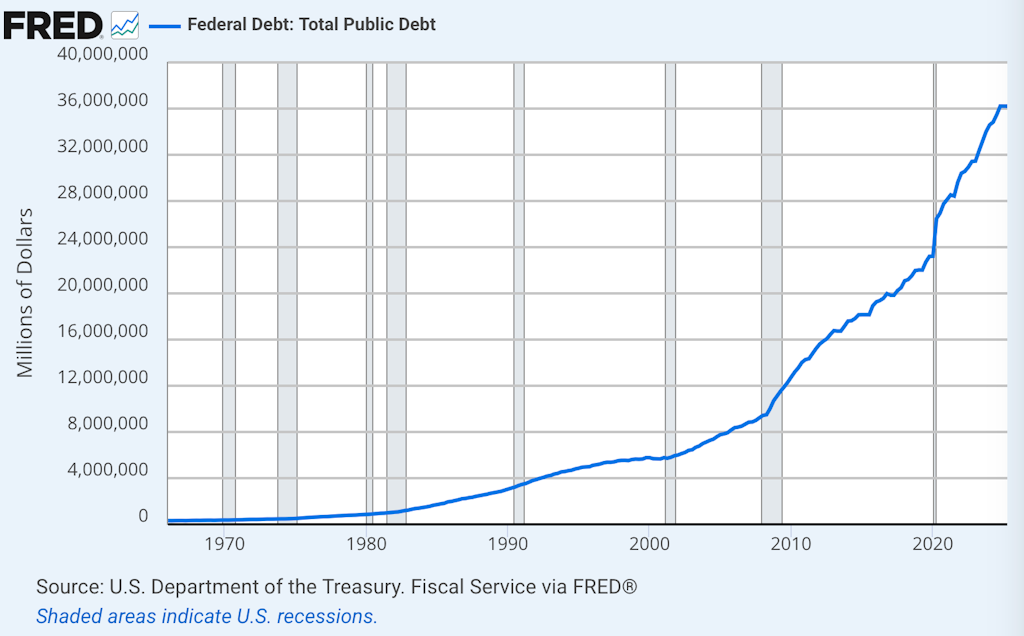

In the time the Federal Reserve responsibly burned $2.4 trillion of reserves, the federal government somewhat irresponsibly added $6 trillion of debt.

George Washington, who used his farewell address to advise that governments’ “vigorous exertions in time of peace to discharge the debts,” would not approve.

Despite a strong economy, the US has made no effort at all to reduce its debt, and that has gotten people worried about fiat money again.

There’s not much the Fed can do about that, because burning bank reserves will never be as convincing as burning tax receipts.

Get the news in your inbox. Explore Blockworks newsletters:

- The Breakdown: Decoding crypto and the markets. Daily.

- 0xResearch: Alpha in your inbox. Think like an analyst.